|

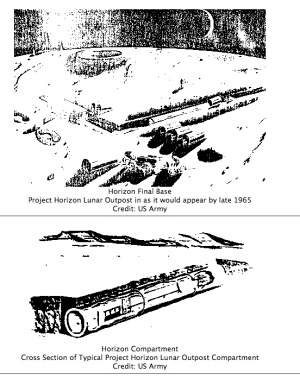

On 20 March 1959, Arthur G. Trudeau, Chief of Research and Development for the U.S. Army, submitted a request for the study to place a lunar outpost on the Moon. The result was Project Horizon, a plan (dated 9 June 1959) to place a military base with 10-20 men on the surface of the Moon by 1965. Full details are in Vol. I and Vol. II (pdf).

The introduction to the proposal stated that the establishment of a lunar base would:

- Demonstrate the United States scientific leadership in outer space

- Support scientific explorations and investigations

- Extend and improve space reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities and control of space

- Extend and improve communications and serve as a communications relay station

- Provide a basic and supporting research laboratory for space research and development activity

- Develop a stable, low-gravity outpost for use as a launch site for deep space exploration

- Provide an opportunity for scientific exploration and development of a space mapping and survey system

- Provide an emergency staging area, rescue capability or navigational aid for other space activity

It further stated the following, prescient about the Soviet manned capability, but extremely optimistic about the timetable for the Moon Base:

Advances in propulsion, electronics, space medicine and other astronautical sciences are taking place at an explosive rate. As recently as 1949, the first penetration of space war accomplished by the US when a two-stage V-2 rocket reached the then unbelievable altitude of 250 miles. In 1957, the Soviet Union placed the first man-made satellite in orbit. Since early l958, when the first US earth satellite was launched, both the US and USSR have launched additional satellites, moon probes, and successfully recovered animals sent into space in missiles. In 1960, and thereafter, there will be other deep space probes by the US and the USSR, with the US planning to place the first man into space with a REDSTONE missile, followed in 1961 with the first man in orbit. However, the Soviets could very well place a man in space before we do. In addition, instrumented lunar landings probably will be accomplished by 1964 by both the United States and the USSR. As will be indicated in the technical discussions of this report, the first US manned lunar landing could be accomplished by 1965. Thus, it appears that the establishment of an outpost on the moon is a capability which can be accomplished.

Underlying all of this was the traditional von Braun team approach:

paramount to successful major systems design is a conservative approach which requires that no item be more “advanced” than required to do the job. It recognizes that an unsophisticated success is of vastly greater importance than a series of advanced and highly sophisticated failures that “almost worked. “

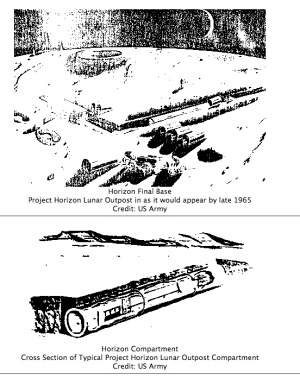

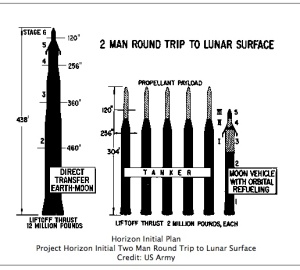

The proposal discusses the ongoing development of the Saturn I by ARPA, expecting it would be fully operational by 1963. The Saturn I stood more than 200 feet tall, and would be superseded by the Saturn II in 1964, standing 304 feet tall. By the end of 1964, a total of 72 Saturn I rockets would have been launched on various programs of discovery, including 40 to support the manned lunar base. In order to support the full complement of 12 men, 61 Saturn I and 88 Saturn II launches would be required by the end of 1966, landing 490,000 pounds of cargo on the lunar surface. 64 launches were scheduled for 1967, landing an additional 266,000 pounds of supplies. The total cost of the eight and one-half year program was estimated to be $6 Billion.

The von Braun team thought very large indeed.

|

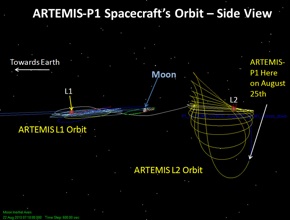

Project Horizon – Lunar Base 1965

Image Credit: US Army

Project Horizon – Rockets

Image Credit: US Army

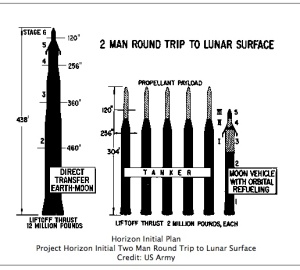

Orbital Trajectories

Image Credit: US Army

|